How an LSD-Spiked Coffee Gave Birth To The Beatles' Revolver

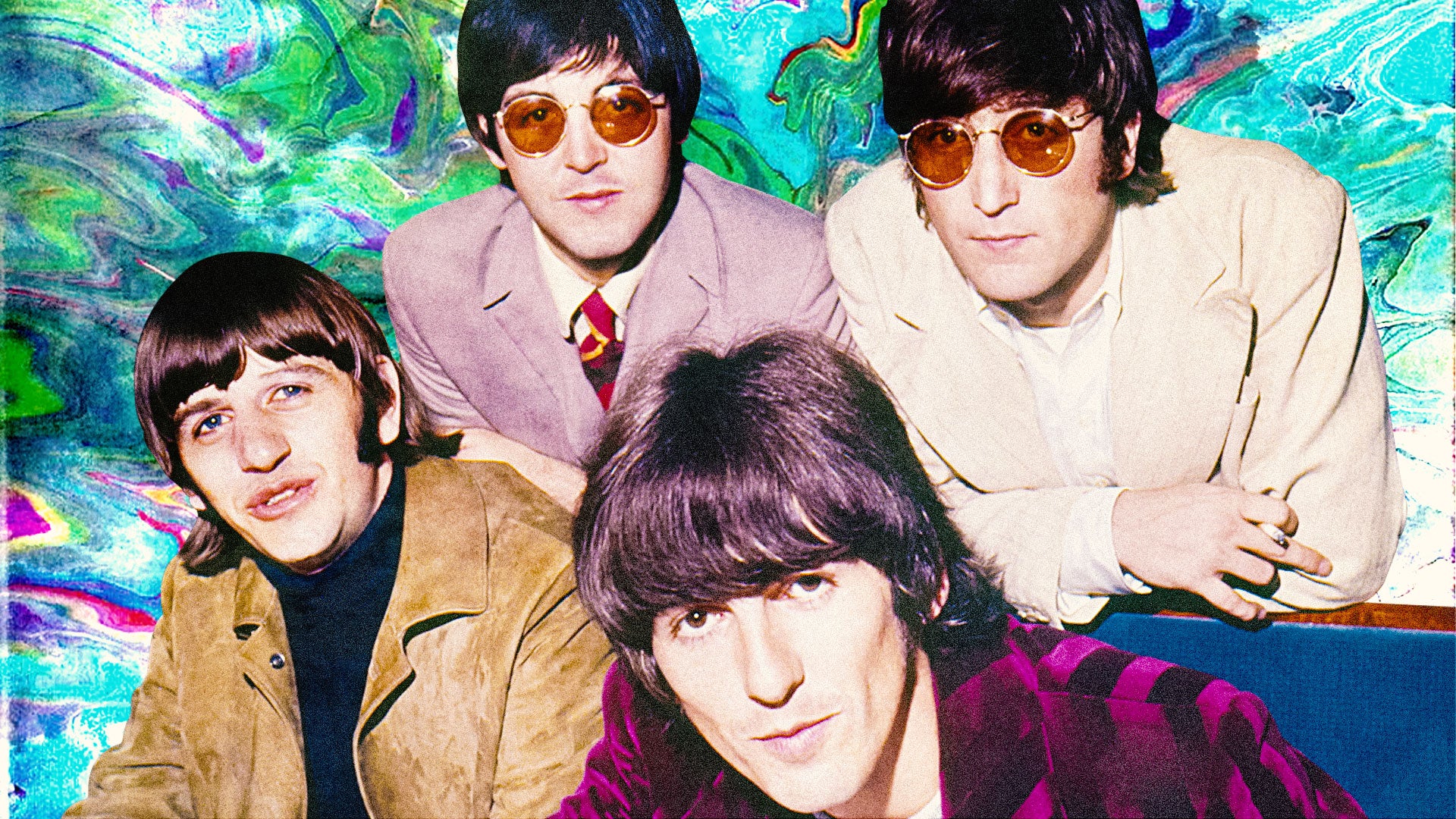

The story of "Revolver" began on a night of chaos and enlightenment. "We've had LSD!" John Lennon told George Harrison.

Spring 1965. Lennon and his wife, Cynthia, along with Harrison and his wife, Pattie Boyd, were at a dinner hosted by dentist John Riley and his girlfriend, Cyndy Bury, at their London home.

Before they left, Riley offered them coffee and insisted they finish it - later revealing to Lennon that he had spiked the coffee with LSD.

Lennon was outraged — "How dare you fucking do this to us?"

He was aware that LSD was a psychedelic that would change perception, emotions, and thoughts radically and could be frighteningly different.

"It was as if we suddenly found ourselves in the middle of a horror film," recalled Cynthia Lennon. "The room seemed to get bigger and bigger." The Beatles and their wives hastily left Riley's home in Harrison's Mini Cooper.

The group then went to the Ad Lib club in Leicester Square. In the elevator, all of them panicked. "We all thought there was a fire in the lift," Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1971. "It was just a little red light, and we were all screaming, all hot and hysterical."

Once inside the club, a sense of calm slowly began to take over. Harrison said, "I had such an overwhelming feeling of well-being, that there was a God, and I could see him in every blade of grass. It was like gaining hundreds of years of experience in 12 hours."

The night ended at the Harrisons' home in Esher, outside London. John later reflected, "God, it was just terrifying, but it was fantastic. George’s house seemed to be like a big submarine... It seemed to float above his wall, which was 18 feet high, and I was driving it. I did some drawings at the time, of four faces saying, ‘We all agree with you.’ I was pretty stoned for a month or two."

This less-than-gentle introduction to LSD would eventually culminate in the creation of "Revolver," the Beatles' most daring and innovative album.

The Beatles became regular marijuana smokers after Bob Dylan introduced them to it in a hotel room in August 1964. The drug influenced the creation of 1965's Rubber Soul, which Lennon referred to as the band’s “pot album,” making it more introspective and mesmerizing.

The musical change within the Beatles was very evident as they were growing bolder and bolder. They had influenced a host of British and American bands, among them the Rolling Stones, the Byrds, and the Beach Boys, with their idiosyncratic chord changes, convolute and angular melodies, and commitment to writing their songs.

McCartney knew the competition was heating up, so he pushed hard to stay a step ahead creatively. Though he had been the most resistant to psychedelia, he now proved to be, in most respects, the most forward-thinking Beatle.

Soon, McCartney became interested in the avant-garde electronic music of a crop of classical composers and experimentalists that included Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, and Edgard Varèse, along with the free jazz of saxophonist Albert Ayler. "I'm trying to catch up on everything I've missed," McCartney said.

"People are saying, painting, writing, and composing amazing things, and I need to be aware of what's happening."

It was in April that McCartney took Lennon to Indica, where they found "The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead," by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert.

It was this book that gave Lennon some framework against which he could understand his experiences with the drug. He read the entire book at the shop. A few days later, Lennon introduced a new song to the Beatles and their producer, George Martin.

This song was initially titled "Mark 1," was later changed to "Tomorrow Never Knows," and started : "Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream/It is not dying, it is not dying/Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void/It is shining, it is shining."

Harrison, then a student of Indian music, contributed a tamboura to generate an ethereal and swirling harmonic background. It was McCartney, though, who conceived the sound representing the meeting between the spirit and the void. He came into the studio one morning with different tape loops he had created overnight; these contained material like guitar-tuning and weird shrieking.

Martin listened to these, playing them forwards and backward, and eventually fed them through a bank of several interlinked tape machines at Abbey Road. Every machine was manned by a different employee of EMI, all of whom changed speed very slightly to set up a collective tic for an otherworldly sound.

This tape collage played as Lennon sang, "Listen to the color of your dreams/It is not living, it is not living."

Their interpretation of soul transmigration was haunting, in some ways convincing—one could almost see an LSD trip.

While bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Doors, and Pink Floyd supposedly indulged in extended improvisation to recreate the experience of LSD, the Beatles worked toward their sound with studied calculation.

"Tomorrow Never Knows" set the tone for the "Revolver" album, challenging the Beatles to be creative. From April 6th to June 22nd, they committed their longest single recording period to date for writing songs in dozens of newly dreamed-up styles.

The backward guitar lines that Harrison developed for "I'm Only Sleeping" were not only experimental compared to all of the previous music but also about most future pop music; it was the craft that gave substance to his vision, from McCartney's upbeat, Motown-inspired "Got to Get You Into My Life" to his melancholy "For No One," with Alan Civil's plaintive French horn solo from the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

This was particularly true of Harrison, who did evidence immense artistic growth. Before "Revolver," he was a minor contributor to the Beatles, overshadowed by the accomplished Lennon and McCartney. His melodies were narrow, as were his lyrics. But during the Beatles' filming of "Help!" in India in 1965, Harrison first heard a sitar played by local musicians.

Fascinated by the fullness and unique sound, through encouragement from David Crosby and Roger McGuinn of the Byrds and sitar master Ravi Shankar, Harrison became quite interested in the instrument. He purchased a sitar and at the urging of Lennon, played it in "Norwegian Wood" on "Rubber Soul."

This experimental sound paved its way throughout rock music as well; for example, even the Rolling Stones used the sitar in songs such as "Paint It, Black."

The sitar and Harrison’s rapid mastery of Indian music gave him new creative freedom within the Beatles. Harrison's first Indian-influenced song, "Love You To," didn't feature significant contributions from the other Beatles; instead, he collaborated with Indian musicians from London’s Asian Music Circle. The song didn't reflect a deep understanding of Hindu beliefs but rather focused on a desire to make love all day, showcasing Harrison’s typical bitterness: “There’s people standing ’round/ Who’ll screw you in the ground/ They’ll fill you in with all their sins, you’ll see.”

Within a year, McCartney tried LSD for the first time, though not with the other Beatles. In a 1967 interview, he stated that the drug “opened my eyes to the fact that there is a God… It is obvious that God isn’t in a pill, but it explained the mystery of life. It was truly a religious experience.”

He also noted LSD’s impact, saying, “It started to find its way into everything we did, really. It colored our perceptions. I think we started to realize there wasn’t as many frontiers as we’d thought there were. And we realized we could break barriers.”

Soon after, the Beatles decided to stop using LSD. However, Lennon, who had used it the most—often to a worrying extent according to Harrison (“We didn’t realize the extent to which John was screwed up”)—didn't always stick to this decision.

In 1968, after a night on psychedelics, Lennon gathered friends at Apple Records and declared he was Jesus Christ returned to Earth and wanted a press release to announce it.

Two days after completing the recording and mixing of Revolver, the Beatles embarked on a world tour. In Germany, they listened to the finished album, and McCartney was momentarily concerned it sounded out of tune. Their music had become so innovative that even McCartney, with his keen ear, found it disorienting.

The tour was a letdown from the start. After three months of creating music that couldn’t be performed live, they were now playing older songs that felt outdated. Worse troubles awaited them.

In Manila, Philippines, manager Brian Epstein declined an invitation to a garden party hosted by the First Lady, Imelda Marcos, leading to a hostile public reaction and their hurried departure from the country. At a London press conference, the band appeared shaken. “We’re going to have a couple of weeks to recuperate,” said Harrison, “before we go and get beaten up by the Americans.”

Harrison’s comment was prophetic. Earlier in March, before starting Revolver, journalist Maureen Cleave had written profiles of each Beatle for the Evening Standard. McCartney used the platform to criticize America’s racism and conformity: “[America’s] a lousy country to be in where anyone who is black is made to seem a dirty nigger,” and “We got rid of that little convention for them.” But it was Lennon’s interview that caused a lasting stir. He said, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock & roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

On July 29th, two weeks before their U.S. tour began, an American teen magazine published excerpts from Cleave’s interviews, highlighting McCartney’s comments about America and Lennon’s about Christianity. While McCartney’s remarks went unnoticed, Lennon’s caused an uproar, especially in the American South, where radio stations announced boycotts and bonfires. The band received death threats.

At a Chicago press conference on August 12th, Lennon, almost trembling, tried to apologize: “I’m not anti-God, anti-Christ or anti-religion. I was not knocking it. I was not saying we were greater or better… I used the word ‘Beatles’ as a remote thing.” He later reflected, “When they started burning our records… that was a real shock. I couldn’t go away knowing I’d created another little piece of hate in the world… so I apologized.”

The controversy arguably overshadowed the Beatles' historic release of Revolver. The album debuted in the U.S. on August 8th and hit Number One, but John Lennon’s comments drew more attention than their new music. Capitol Records, their American label, didn’t help maintain the album's integrity, removing “I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Doctor Robert” for the U.S. version and placing them on another album, Yesterday and Today, released in mid-June.

Capitol released “Yellow Submarine” and “Eleanor Rigby” as a double A-side single. “Yellow Submarine,” perceived as a children’s song but later symbolic at anti-war rallies, reached Number Two, while “Eleanor Rigby” peaked at Number 11. Their failure to reach Number One could be attributed to their unprecedented sound for the Beatles or the backlash from Lennon’s remarks.

Nonetheless, both songs dominated Top 40 radio for weeks, with “Rigby” particularly subversive. “Eleanor Rigby” tells the story of a lonely woman and a parson, Father McKenzie, whose futile sermons went unheard. In the end, Eleanor dies, and McKenzie buries her, with the stark line “No one was saved.” This imagery, slipped into public consciousness with a classical string octet, echoed Lennon’s sentiment that Christianity offered cold comfort, with no salvation for the lonely or faithful, a revelation overlooked by critics.

The religious controversy, limitations of their live performances, and the mix of anger and acclaim took a toll on the Beatles that summer. Danger felt close, and the joy was gone. The band played their final concert on August 29th, 1966, at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. On the flight home, Harrison declared, “Well, that’s it. I’m not a Beatle anymore.”

Months later, McCartney hinted at a possible breakup in a January 1967 interview, saying, “We’ve all grown up in a childish way. Now we are ready to go our own ways. We’ll work together only if we miss each other… I’m no longer one of the four moptops.” Although a ruse, as the Beatles were already recording a new album, it was true they could no longer be what they once were.

After the U.S. tour, McCartney wrote the soundtrack for The Family Way, and George Harrison spent six weeks in India studying sitar with Ravi Shankar and delving into Hindu beliefs. Starr visited Lennon in Spain, where he was filming How I Won the War. Lennon found the experience tedious and lonely. When the Beatles reconvened in fall 1966, they looked and sounded transformed, sporting mustaches and bohemian attire, with new songs reflecting their changed lives.

McCartney introduced more complex arrangements in “She’s Leaving Home” and “A Day in the Life,” while Harrison’s embrace of Eastern philosophy and Hindustani classical music shone in “Within You Without You.”

However, it was Lennon’s “Strawberry Fields Forever,” begun in Spain, that amazed the Beatles and producer George Martin. They spent a month recording it, aiming to make it the strangest pop song ever, though it was eventually released as a single in February. The album resulting from these sessions, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, marked the Beatles' greatest artistic leap and epitomized psychedelic imagination.

By 1967, psychedelia took on a more positive tone, exemplified by “All You Need Is Love.” The Beatles' collaborative process changed as each member brought in their own songs, increasingly becoming each other's accompanists. Their collective unity began to fragment.

Lennon’s vision in 1965 of them sailing together in mutual sanctuary set in motion a turbulent journey. Revolver marked a turning point, splitting the Beatles' story in two: the sensational act ended, and something unforeseen began. By the end, the four no longer wanted to look at each other.

Comments